Newspaper Feature

Herald, Saturday, 29 November 1941, p. 14

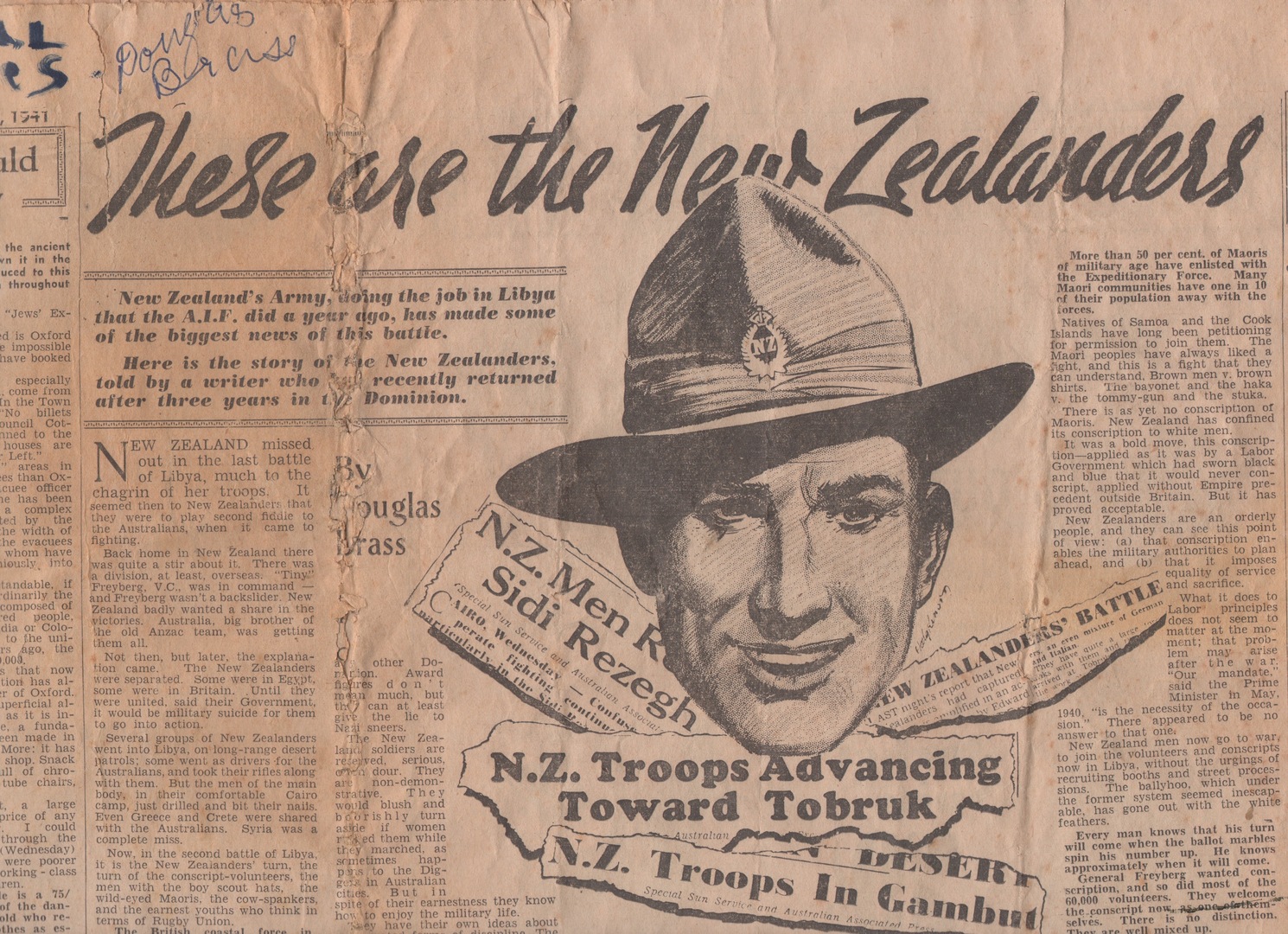

In November 1941, New Zealand-born journalist Douglas Brass wrote a major column for the Herald in Melbourne. Spread over five columns, with a large banner headline and a striking illustration, it was published during the very week when New Zealand forces were receiving major headlines internationally for leading the Allied assaults at Sidi Rezegh and Belhamed to relieve the Libyan port town of Tobruk.

New Zealand’s Army, doing the job in Libya that the A.I.F. did a year ago, has made some of the biggest news of the battle.

Here is the story of the New Zealanders, told by a writer who has recently returned after three years in the Dominion.

NEW ZEALAND missed out in the last battle of Libya, much to the chagrin of her troops. It seemed then to the New Zealanders that they were to play second fiddle to the Australians, when it came to fighting.

Back home in New Zealand there was quite a stir about it. There was a division, at least, overseas. ‘Tiny’ Freyberg, V.C., was in command – and Freyberg wasn’t a backslider. New Zealand badly wanted a share in the victories. Australia, big brother of the old Anzac team, was getting them all.

Not then, but later, the explanation came. The New Zealanders were separated. Some were in Egypt, some were in Britain. Until they were united, said their Government, it would be military suicide for them to go into action.